What are the concepts of Stress and Strain?

When we apply an external force on a solid object, it may get deformed – though this deformation may or may not be visible to our naked eye. How much an object will get deformed will depend on:

- The nature of the solid object.

- The amount of external force exerted.

As we know, every action has an equal and opposite reaction. So, when we apply an external force on a solid object, a restoring force is developed in the body, which is equal in magnitude but opposite in direction to the externally applied force.

If you have understood it this far, we can now move on and study the concepts of Stress and Strain.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents- What is Stress?

- What is Strain?

- Longitudinal Stress and Strain

- Shearing Stress and Strain

- Hydraulic Stress and Volume Strain

- Hooke’s Law

What is Stress?

Stress is the restoring force applied per unit area of cross section of the deformed body. So, if force F is applied on A area of cross section, then:

Magnitude of Stress = \( \frac{F}{A} \)

The SI unit of stress is \(N/m^2\) or Pascal (Pa).

What is Strain?

Strain is the fractional change in length, area, shape, or volume of a solid object. So, it is a ratio, and so it has no unit or dimension.

We can infer from the definition of Strain that there must be various ways in which an object may be deformed (i.e. its dimensions changed) by an external force. Let’s see some of these ways.

Longitudinal Stress and Strain

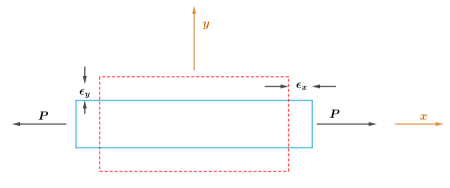

When two equal and opposite external forces are applied perpendicular to the cross-sectional area of a cylinder, then we encounter the concepts of Longitudinal Stress and Longitudinal Strain.

Longitudinal Stress

It is the restoring force per unit area, when a cylinder is subjected to two equal and opposite forces applied normal to its cross-sectional area.

- If these forces stretch the cylinder, then we call it tensile stress.

- If these forces compress the cylinder, then we call it compressive stress.

Longitudinal Strain

Whether a cylinder is subjected to tensile stress or compressive stress, there will be a change in the length of the cylinder (increase or decrease).

If L is the original length of the cylinder, and ΔL is the change in the length, then:

Longitudinal strain = \( \frac{ΔL}{L} \)

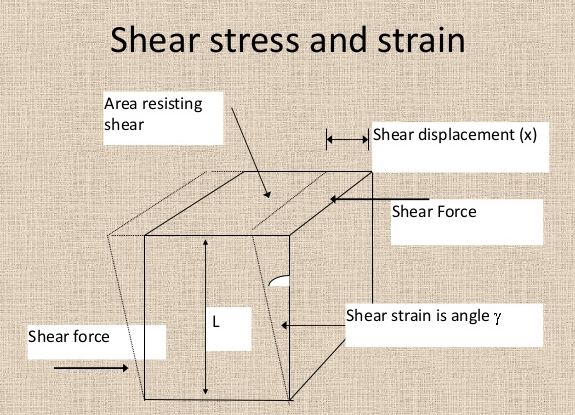

Shearing Stress and Strain

When two equal and opposite external forces are applied parallel to the cross-sectional area of a cylinder, then we encounter the concepts of Longitudinal Stress and Longitudinal Strain.

Here, the cylinder will not be elongated or compressed, but rather there will be relative displacement between the opposite faces of the cylinder. For example, when we press our hand on a book and push it horizontally.

Shearing Stress

It is the restoring force per unit area, when a cylinder is subjected to two equal and opposite forces applied parallel to its cross-sectional area. As the applied forces are tangential, we also call this tangential stress.

Shearing Strain

Shearing Strain is the ratio of the relative displacement of the faces Δx to the length of the cylinder L.

Shearing Strain = \( \frac{Δx}{L} \)

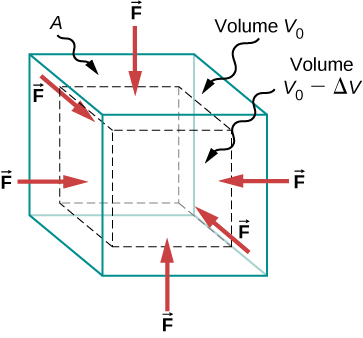

Hydraulic Stress and Volume Strain

When a solid body is put under a stress that is equal and normal to its surface at every point, then it’s called Hydraulic Stress.

Such a stress deceases the volume of the solid in such a manner that the geometrical shape of the object does not change.

For example, when we submerge a solid cube under water, the water compresses it uniformly on all sides. The force applied by the water (and the stress applied by the cube) is in perpendicular direction at each point of the surface. The cube will decrease in volume, but its shape will not change.

Hydraulic Stress

It is the internal restoring force per unit area, which is equal in magnitude to the external hydraulic pressure (applied force per unit area).

Volume Strain

Volume Strain is the ratio of change in volume (ΔV) to the original volume (V).

Volume strain = \( \frac{ΔV}{V} \)

Obviously, it is caused by external hydraulic pressure.

Hooke’s Law

Hooke’s Law states that stress and strain are proportional to each other. That is, they have a linear relationship.

That is, stress α strain

Or stress = k × strain

where k is the proportionality constant and is known as modulus of elasticity.

Note

NoteHooke’s law is an empirical law. That is, it has been derived using a lot of data sets, and so it is valid for most solids/materials. However, not all materials follow this law, i.e. in case of some solids stress α strain is not true.

Now, let us study modulus of elasticity in more detail.

Types of Modulus of Elasticity

There are many types of moduli of elasticity, e.g. Young’s Modulus, Shear Modulus, Bulk modulus of elasticity and Modulus of rigidity. But among these Young’s Modulus is the most significant and this is what we are going to study in detail.

Young’s Modulus

Earlier we saw that, stress = k × strain, where k is the modulus of elasticity.

So, k = \( \frac{stress}{strain} \)

Young’s modulus is the ratio of the longitudinal stress (σ) to the longitudinal strain (ε). It is denoted by the symbol Y or E.

So, Y = \( \frac{Longitudinal \hspace{1ex} Stress}{Longitudinal \hspace{1ex} Strain} \)

Note

NoteLongitudinal Stress can be tensile stress or compressive stress. Experiments have shown that for a given material, tensile stress and compressive stress are the same. So, we will just use the term longitudinal stress.

Young's Modulus of various solids

Young's Modulus of various solidsMetals have higher values of Young’s moduli. It means that a large external force is required to make even small changes in their length.

Descending order of the magnitude of Young’s moduli has been given below for some metals:

Steel > Copper > Brass > Aluminium

It means that steel is more elastic than copper, brass, or aluminium. It’s even more elastic than rubber. That’s why we use it in heavy-duty machines and in structural designs.

Non-metals, such as wood, bone, concrete and glass have even lower Young’s moduli.

Some random facts

Some random factsBreaking Stress: It is the minimum stress required to break a wire. It’s constant for a given material. But we know that Stress = F/A, i.e. it’s force per unit area. That is, more the area of cross-section of a wire, more the force we will need to exert to break it. So, to break a thick wire we will need to exert more force. We can see that, for a given material breaking stress is fixed, but breaking force varies with change in area of cross-section of the wire.

To produce the same twist in a cylinder, we need to exert more torque on a hollow cylinder, than what is required in case of a solid cylinder. So, hollow shaft is stronger than a solid shaft.

Elastic Fatigue: When we apply repeated alternating deforming force on an elastic body, its behaviour becomes less and less elastic with time. This phenomenon is called as Elastic Fatigue. Eventually, it may cause a material to break. That’s why we abandon steel bridges after some time, as steel gets less elastic with time due to it being exposed to continuous stretching and bending caused by passing vehicles, winds, earthquakes, etc.

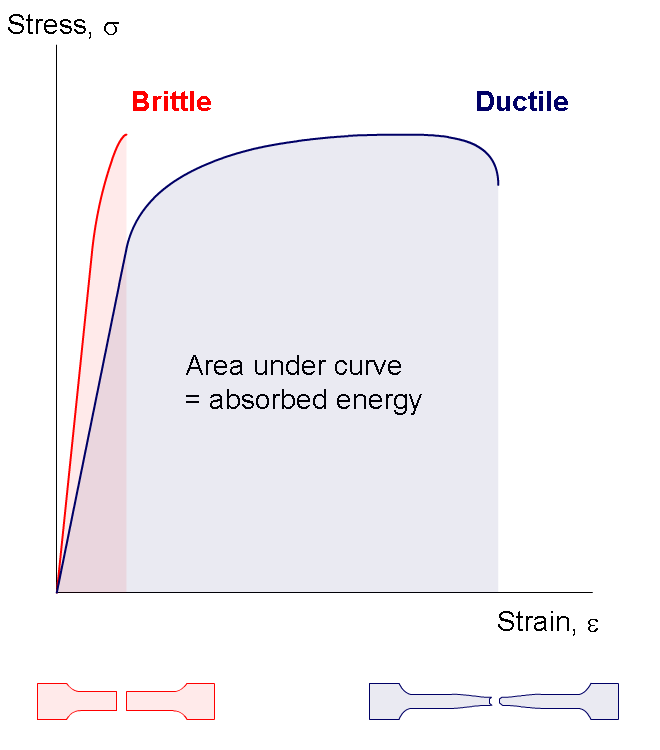

What are Ductile and Brittle Materials?

What are Ductile and Brittle Materials?To understand the difference between Ductile and Brittle Materials, we need to understand two terms.

Elastic limit: When we stretch a material by applying an external force, it tries to go back to its original position/state. Elastic materials have larger elastic limit. But when a material is stretched beyond its Elastic limit, it cannot go back to its original state. It remains stretched to a certain extent.

Fracture point: Every material can be broken once we apply sufficient amount of force to stretch it. This is called the Fracture point.

Ductile materials can suffer large deformations beyond their elastic limit, without breaking. That is, the difference between their elastic limit and fracture point is large.

However, if the difference between the elastic limit and fracture point of a material is small, we call such material brittle. Such materials break pretty soon after crossing their elastic limit.