Various Models of the Structure of Atom

In this article, we are going to learn about the various models that were proposed to explain the structure of an atom.

Various models were proposed to explain the structure of atom. They were more in the nature of hypothesis, which tried to explain the results we saw in our experiments.

With time critics pointed out lacunae with a particular model, which forced theoretical physicists to come up with a better explanation or hypothesis. This process kept on repeating for long, and is still ongoing.

Though unlike old times, now we have developed strong electron microscopes that allow us to take pictures of even an atom. But still the true nature of matter is still a puzzle for us.

But let’s not put the cart before the horse. Let us first study the various popular models that were proposed to explain the structure of atom, and the reasons behind their downfall.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents- Some Background

- Thomson’s Atomic Model

- Ruterford’s Atomic Model

- Bohr’s Atomic Model

- Quantum Mechanics Model

Some Background

At the start of the 19th century, scientists knew these things:

In 1897, English physicist J. J. Thomson (1856 –1940) found that various atoms contain electrons that are negatively charged. But atom as a whole is neutral. So, there must be some other particle(s) inside an atom that is positively charged, and can neutralize the negative charge of the electrons. So, scientists at that time were trying to find positive particles inside an atom.

The mass of electron was found to be thousands of times lighter than the mass of the entire atom. So, scientists knew that there must be other particles inside an atom that are much heavier than an electron – something that gives an atom most of its mass.

The radius of the atom was estimated to be of the order of 10-10 meter. (They used kinetic theory of matter to reach to this estimate).

Once it was clear that atoms are made up of yet smaller particles (e.g. electrons, etc.), the race to find and explain those particles began. And many models were proposed to explain how they are placed inside an atom, i.e. how an atom is structured.

Let’s study some of these proposed models.

Thomson’s Atomic Model

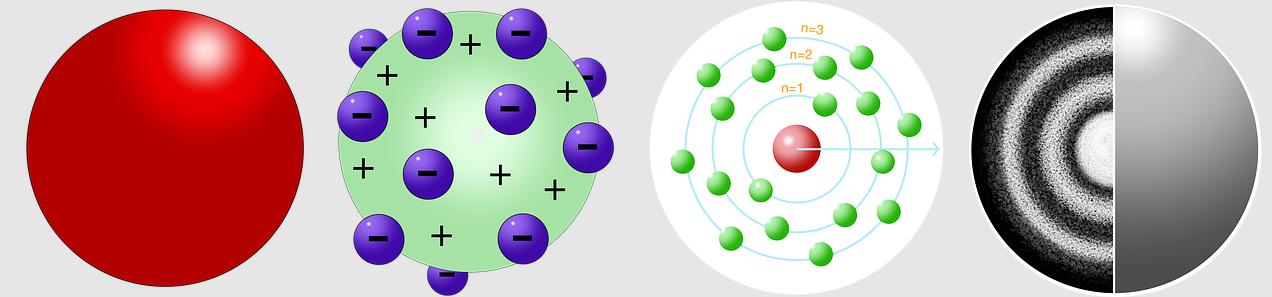

J. J. Thomson proposed the first model of atom in 1898. It is also called as Watermelon model, or Plum Pudding model.

As per this model:

- Positive charge inside an atom is uniformly distributed all across the atom.

- Electrons, which have a negative charge, are embedded in it, just like the seeds of a watermelon.

Reasons for rejection of Thomson’s Atomic Model

The main reason for the downfall of this model was that it was not able to explain the observations of some experiments – especially the ones conducted by Ernst Rutherford (1871–1937), who was a former research student of J. J. Thomson.

It was observed that when we fire α-particles on elements, most of them pass through but some α-particles deflect by pretty large angles. It means that there’s something inside an atom that is pretty small but has all the positive charge concentrated in it. The positive charge is not scattered evenly throughout the volume of an atom, as suggested by Watermelon model of atom.

The Experiment

The ExperimentThe details of Ernst Rutherford’s experiments are as follows.

He was shooting α-particles at various metallic foils. Then he used to record where those α-particles ended up – were they stopped, do they just pass through, or get deflected?

All this was being done to find new insights regarding the structure of an atom.

His Observation:

Most of the α-particles just passed through the metallic foil undeviated, like it was nothing. It showed that most of the atom is hollow. The whole of the atom is not filled with positive charge as J. J. Thomson suggested.

But some α-particles did get deviated, some by pretty large angle. As α-particles are positively charged, the reason for their deviation must have been an encounter with another positively charged entity that must have pushed them away due to strong electrostatic repulsion – thus nucleus of an atom was discovered by him, and the fact that it is positively charged.

So, after dismissing the model given by J. J. Thomson, Ernst Rutherford proposed one of his own.

Rutherford’s Atomic Model

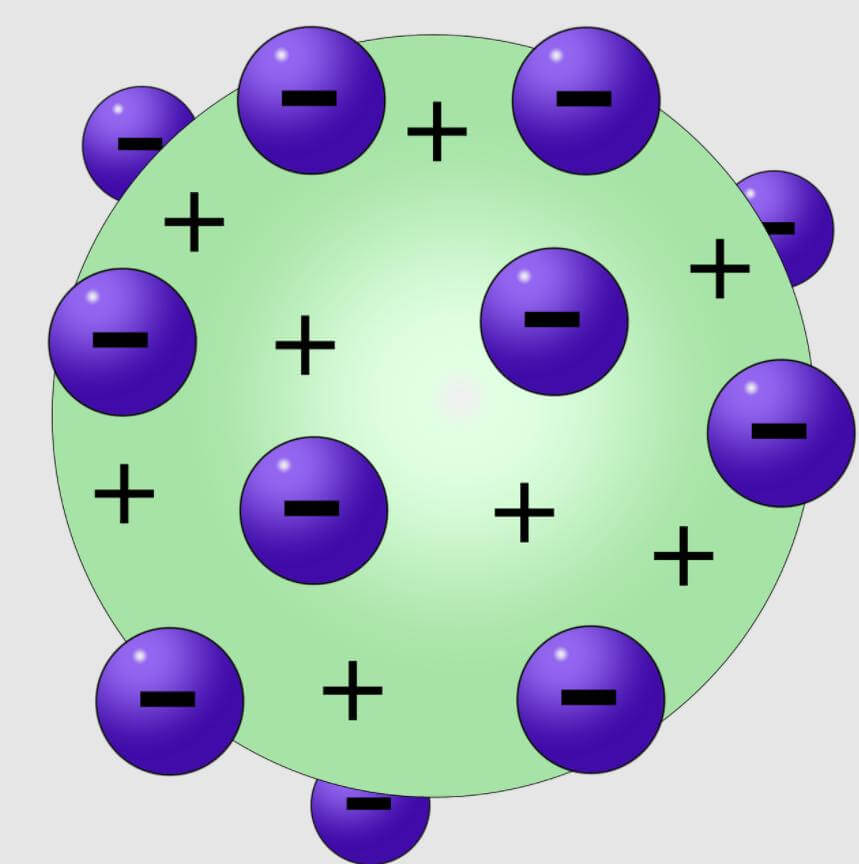

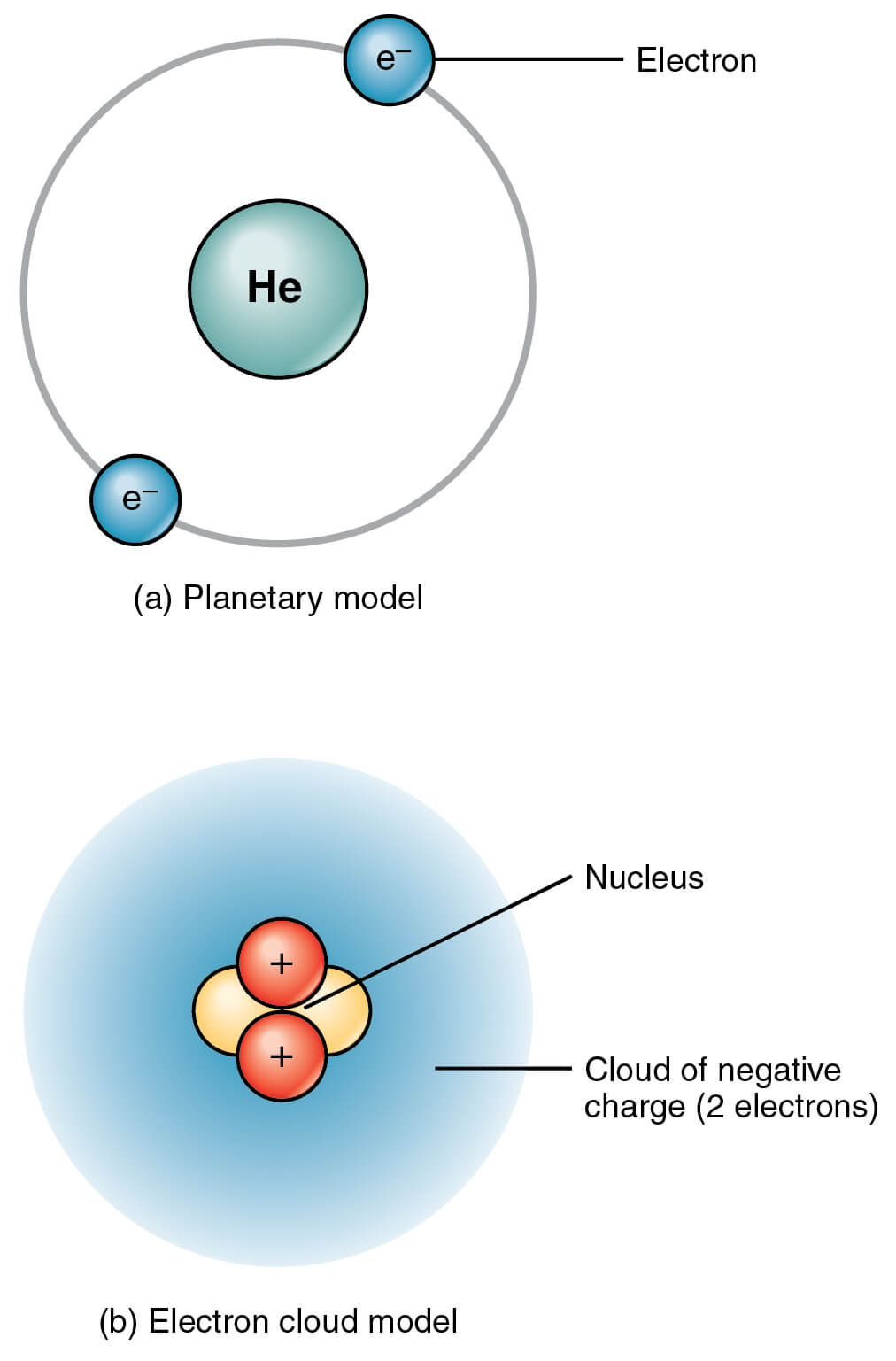

The second, and more successful model for the structure of an atom was given by Ernst Rutherford (1871–1937). It is called Rutherford’s Planetary model of atom or Nuclear model of atom.

In fact, as mentioned above, it was his experiment that proved that Thomson’s Atomic Model cannot be correct.

As per this model:

- There’s a small, highly dense and positively charged region at the center of the atom, called nucleus.

- Nucleus has all the positive charge and almost all the mass of the atom.

- Nucleus is made up of protons and neutrons.

- Negative charged electrons revolve at a very high speed around the positively charged nucleus in circular orbits. There’s a lot of space between the orbits of different electrons. So, major part of an atom is empty space. This is akin to our solar system, where planets revolve around the Sun – hence the name “Rutherford’s planetary model”.

- However, unlike planets and Sun that are attracted towards each other due to gravity, negatively charged electrons and positively charged nucleus are connected via electrostatic force of attraction between them. This holds the atom together.

Reasons for rejection of Ruterford’s Atomic Model

This model is very close to the present conception of atom. Though it had many drawbacks which led to its rejection and improvement by other scientists. Let’s see the reasons behind its rejection.

Stability of atoms

Ruterford’s Atomic Model was not able to explain the stability of atoms.

As per Ruterford’s Atomic Model, electrons are revolving around nucleus. Such revolving electrons will constantly be accelerated towards the nucleus due to centripetal force.

Now, as per classical electromagnetic theory, any accelerated charged particle radiates out (and thus loses) energy. So, these electrons should constantly radiate/emit energy in the form of electromagnetic waves.

As electrons lose energy, they would slow down. This will cause them to spiral towards the nucleus and eventually fall into it. The atom will collapse.

If this is the case, then no atom should be stable – the universe, as we know it, should not exist. But we know for certain that this is not the case.

Emission of lights of discrete wavelengths

Ruterford’s Atomic Model was not able to explain why atoms emit light of certain discrete wavelengths only.

If electrons lose energy and slow down on a continuous basis, then the radii of their orbit should decrease slowly on a continuous basis too. So, as per Ruterford’s Atomic Model an electron can revolve around the nucleus in orbits of all possible radii. This should cause them to emit continuous radiations of all possible frequencies.

However, it has been observed through experiments that atoms emit:

- radiation of only certain fixed frequencies (not all frequencies)

- in discrete form (not continuous form)

These reasons were enough to discard this model.

Concept of Atomic Spectra

Concept of Atomic SpectraWhen we excite the atoms of an element, they emit radiations of certain specific wavelengths only. This set of emitted wavelengths is called the Atomic Spectra or Atomic Spectrum or Emission line spectrum of that element.

Do you want to see how it looks like?

Here’s the Emission line spectrums of Hydrogen and Helium atoms:

Though it will be different for different elements, to untrained eyes it looks the same – many bright colourful lines on a dark background.

Here’s the Emission line spectrum of Hydrogen atom in more detail:

This spectrum is different for each element and so by just analyzing this spectrum we can find out what element we are dealing with. For example, by analyzing the light coming from a star, scientists can tell what kinds of elements are present in that star.

So, Atomic Spectra of an element is like a fingerprint. This discovery was made in the early nineteenth century. Scientists excited atomic gas or vapour kept at low pressure by passing an electric current through it. They found that each element is associated with a characteristic spectrum of radiation.

Emission of specific wavelengths by atoms show that this spectrum of radiation is somehow related to the internal structure of the atom.

Concept of Absorption Spectrum: Just as we have Emission line spectrum of an element, we also have Absorption Spectrum of an element. When white light is passed through the gas of an element, and then the transmitted light is observed via a spectrometer, we find that there are some dark lines in the spectrum. This is the absorption spectrum of that element.

And the fascinating fact is that, this absorption spectrum overlaps exactly over the emission spectrum. That is, the dark lines in absorption spectrum of an element are exactly at the same place where bright lines (wavelengths) were in the emission spectrum of that particular element.

Bohr’s Atomic Model

This model proposed by Niels Bohr in 1913, is also known as Quantum Atomic Model, as it was the first atomic model that made use of the principals of Quantum Physics.

Note

NoteQuantum Physics was very new at that stage and its concepts were still being built (this process is still ongoing though). So, Bohr’s model can at best be called a semi-classical picture of the structure of atom, rather than calling it Quantum Atomic Model in true sense.

Niels Bohr understood from the failure of Ruterford’s Atomic Model, that established principles of classical mechanics and electromagnetism at that time would not be able to explain the structure of quantum level entities like an atom, or explain the observations of the experiments mentioned earlier.

However, he did agree with Ruterford to a certain degree, as he admitted that:

- atom is made up of nucleus and electrons.

- nucleus is made up of protons and neutrons. Protons have positive charge, while Neutrons have no charge. That makes the nucleus positively charged.

- in an atom the number of electrons is always equal to the number of protons. As electrons and protons have equal negative and positive charge respectively, an atom is electrically neutral as a whole.

But then he added some new ideas from quantum physics to explain the stability of an atom and the emission of discrete spectral lines.

He gave his theory in the form of three postulates. Let’s study them one by one.

Bohr’s First postulate

Bohr’s First postulate was regarding stable orbits and stationary states of the atom.

Concept of Stable Orbits: As per him there are certain orbits or energy levels around the nucleus that are stable, i.e. electrons can revolve around the nucleus in these orbits without having to emit any energy. (This was against the principals of electromagnetic theory prevalent at that time.)

Concept of Stationary States of the atom: If electrons in an atom are in these orbits then that atom will remain stable. So, an atom have certain stable states (called stationary states of the atom), and every such state has s definite total energy associated with it.

Electronic Configuration

Electronic ConfigurationNow, let’s understand the concept of Stable Orbits in a little more detail.

Electrons revolve around the nucleus in various stable orbits. Each orbit has a certain energy level and they can hold only a certain maximum number of electrons.

This arrangement of electrons in the various energy levels within an atom is called Electronic Configuration.

These orbits or shells are denoted by numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 or by the letters K, L, M, N, O and P. The maximum number of electrons that an orbit can hold can be given by the following formula:

Maximum number of electrons in an orbit = 2n2, where n = orbit number

The innermost orbit is numbered 1 or denoted by the letter K. This orbit, which is closest to the nucleus, has the lowest possible energy. So, it can hold a maximum of 2 electrons.

The next orbit is numbered 2 or denoted by the letter L. It can hold a maximum of 8 electrons.

The next orbit is numbered 3 or denoted by the letter M. It can hold a maximum of 18 electrons.

The next orbit is numbered 4 or denoted by the letter N. It can hold a maximum of 32 electrons.

and so on.

For example, Sodium (Na) has 11 protons and 11 electrons. So, n = 11. So, its orbits will look like this:

- K orbit: 2 electrons

- L orbit: 8 electrons

- M orbit: the last remaining 1 electron (Valance electron)

Let’s consider one more example. Aluminum (Al) has 13 protons and 13 electrons. So, n = 13. So, its orbits will look like this:

- K orbit: 2 electrons

- L orbit: 8 electrons

- M orbit: the last remaining 3 electrons (Valance electrons)

Bohr’s Second postulate

Bohr’s Second postulate was regarding energy levels of these stable orbits of the electrons around the nucleus.

Every stable orbit is associated with a certain amount of energy. Electrons are found in only those orbits wherein the angular momentum is some integral multiple of h/2π where h is the Planck’s constant (= 6.6 × 10-34 joule-seconds).

Angular momentum of an orbit = n (h/2π), where n = 1, 2, 3, ….

So, the angular momentum of the orbiting electron is quantised.

- The innermost orbit has n = 1, and so its angular momentum is h/2π, i.e. the lowest.

- The next orbit has n = 2, and so its angular momentum is 2h/2π = h/π.

- and so on.

Obviously, the outermost orbit will have the maximum energy.

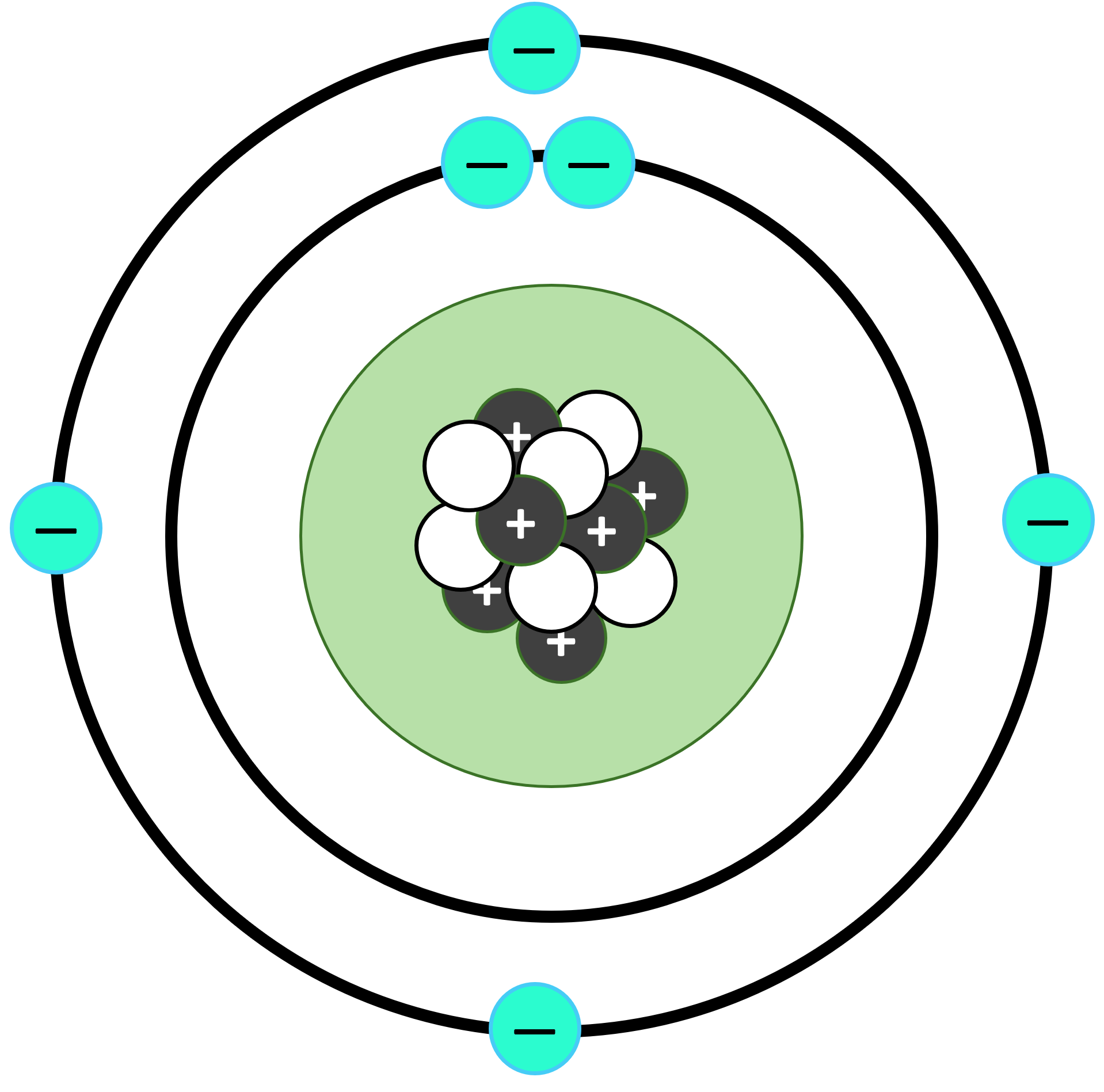

Bohr’s Third postulate

Bohr’s Third postulate was regarding energy change in energy levels of electrons.

We already know that electron in a stable orbit do not lose or gain energy. However, if it jumps from one orbit to another, then its energy changes.

For example, if an electron jumps from an outer high energy orbit to an inner low energy orbit, then it will emit a photon. The energy of that photon will exactly be equal to the energy difference between the two orbits.

We can represent it using an equation.

The frequency of the emitted photon, hν = Ei – Ef

Where Ei is the energy of the initial outer orbit/state, and Ef is the energy of the final inner orbit/state

Note

NoteBohr’s third postulate was inspired by the quantum concepts developed by Planck and Einstein.

Objections against Bohr’s Atomic Model

- The assumptions made by him were entirely arbitrary. It was as if his only goal was to justify the experimental observations.

- It could not explain intensity of the spectral lines, and fine structure of spectral lines.

- This theory was valid only for one-electron atoms/ions. It could not be applied to complex atoms having multiple electrons, i.e. this theory could not be generalized. It failed to provide a proper explanation of the spectra produced by complex atoms.

To fulfil these lacunae a new theory was proposed, called Quantum Mechanics Model, which (as the name suggests) was based on Quantum Mechanics.

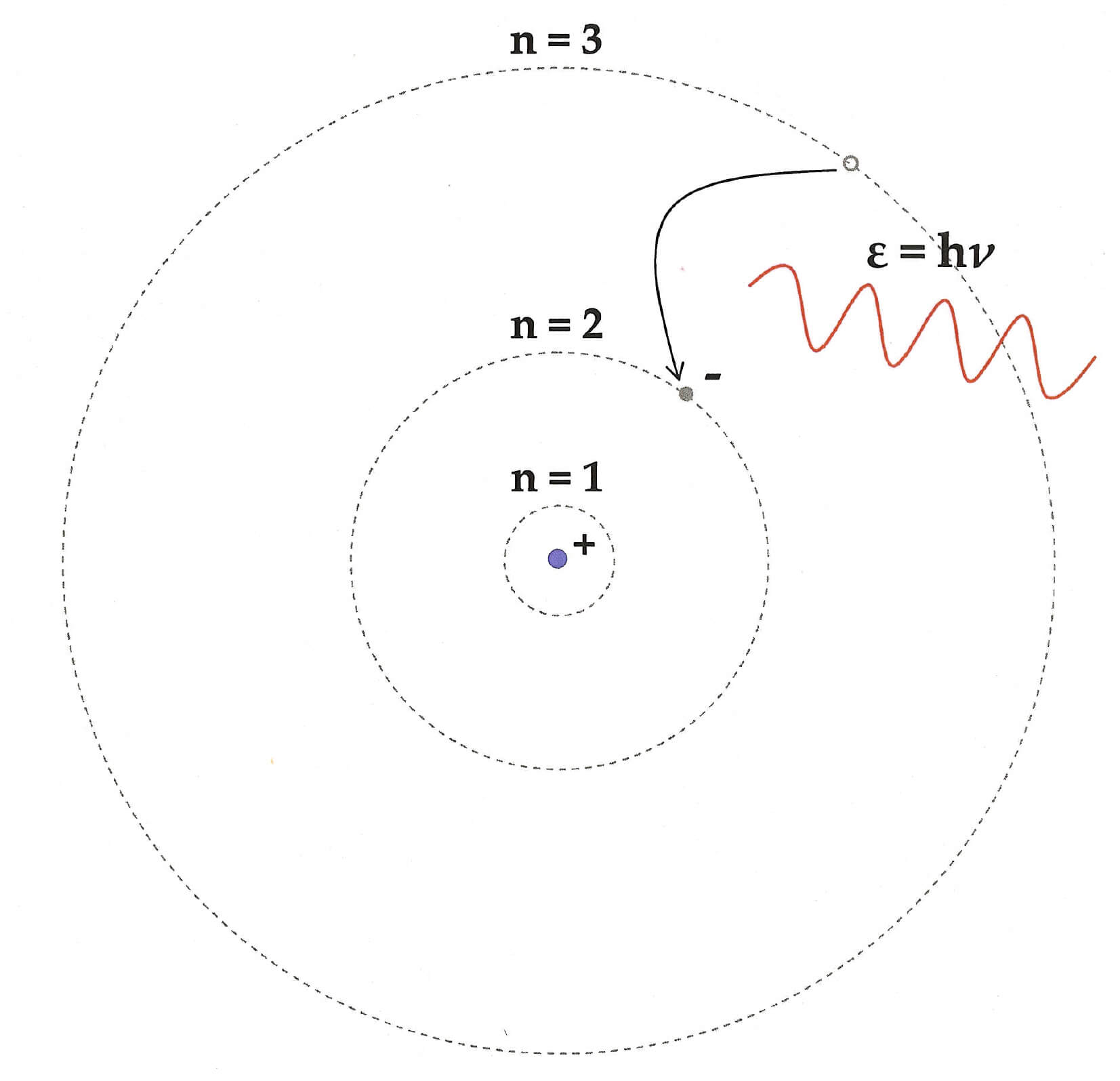

Quantum Mechanics Model

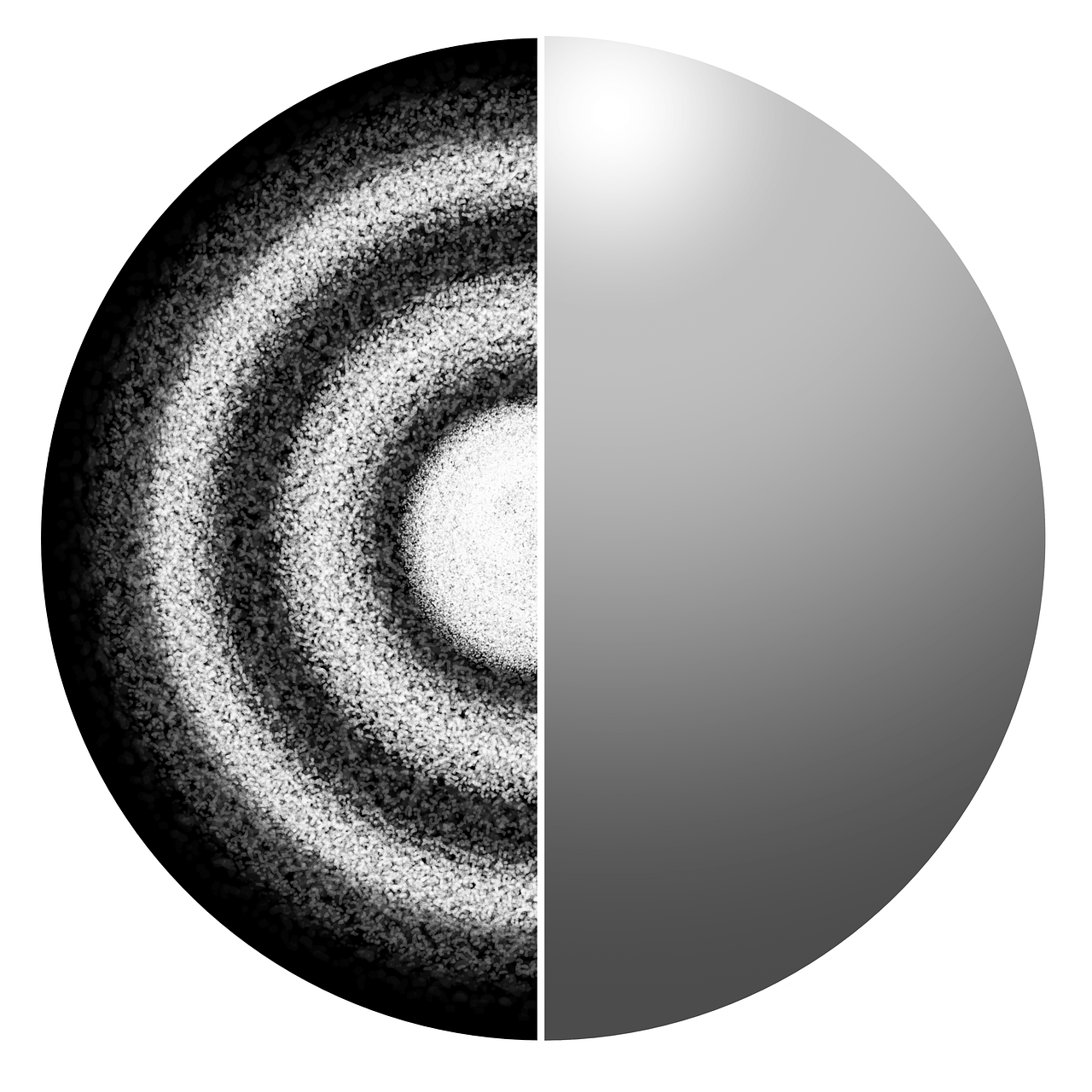

This model is pretty similar to Bohr’s model, with one major difference – Here, the electrons are not confined to certain fixed orbits.

They are all around the nucleus as a probability cloud. That is, it is impossible to predict both the position and the momentum of electrons at a given point of time. That’s why it’s also called as the Electron Cloud Model.

Concept of Orbital

Concept of OrbitalQuantum physics tells us that quantum particles like electrons have properties of both a particle and a wave (called dual properties). Schrödinger wave equation assign a wave-like description to the electrons in an atom.

As waves, electrons can be anywhere in a certain region around the nucleus. Where that electron might actually be is a matter of probability. (As opposed to particle nature of electrons in Bohr model, wherein electrons orbit around the nucleus in definite circular orbits)

To find out this probability we use Orbital, which is a one-electron wave function. This function depends only on the coordinates of the electron.

However, the concept of Orbital is totally different from Bohr’s concept of definite orbits. Orbital is a concept related to wave nature of electrons, while Orbit was a concept related to particle nature of electron.

This model of the structure of atom is currently considered the most accurate representation of an atom.

Well, it’s ironical that we started this journey of understanding the structure of atom with Thomson’s Atomic Model, which considered it as electrons embedded in a positive charged watermelon. And now we consider atom to be a cloud of negatively charged electrons, with a positively charged nucleus embedded at its center.

Vector Model

Vector ModelVector Model was also a model proposed to cover the drawbacks of Bohr’s Atomic Model. It is considered as an extension of the Rutherford-Bohr atom model to multi-electron atoms.

It is a model of the atom in terms of angular momentum.